My mother, Shirley, was born in Middletown, Ohio, just north of Cincinnati, the daughter of a World War I veteran and a very independent-minded mother. Nancy and John were surrounded by her parents, the Schraffenbergers, a family of practical second-generation immigrants, who raised their eyebrows when John began sending home his Army pay to Nancy. She took the money and bought their bedroom furniture. Their post-war wedding came close to an elopement, an event met, I imagine, by pressed lips and sensible skepticism. Their Roaring Twenties were spent quietly with John running a men’s clothing store at the Manchester Hotel. Nancy worked there and in her brother’s flower shop just two doors down from the house on Main. Their hard work probably went a long way to erase the frowns of the Schraffenberger matriarchs. John and Nancy socialized in the company of other veterans and their wives, John twice being commander of the local Legion and organizing suppers and carnivals at the Legion Hall.”They were men who liked to have a good time,” my mother recalls, but remembers her father as only a social drinker, making beer in the basement with his legionnaire buddy, Ron Gill.

“My father was quite a cut-up,” she says, recalling him and his staff pitching pennies behind the counters of the clothing store, the losers being sent out for coffee and snacks. “Some days after school, I would walk up toward the hotel to meet him coming home. I could reach my hand into his deep coat pockets and find a treat there, a piece of hard candy or chocolate from the gift shop.”

But the World War claimed one of its final victims. John had been sick off and on ever since his return, and he died when Shirley was twelve of complications from the gas that had swirled, low and deadly, through a forgotten European trench. My mother remembers a brief time when her father was lying sick in the back bedroom. She would go into to visit him, and sometimes he wouldn’t know her. Toward the end, she remembers traveling with her mother to the Veterans Administration hospital up in Dayton.

“She loved my father so much, she would have died on the spot to keep him alive,” she told me.

My mother doesn’t recall whether she went to her father’s funeral. The family spoke little about the 35-year-old widow’s lengthy stay in a local hospital. “Attempted suicide” was never mentioned but there was whispered talk of “barbiturates.” I wonder how my mother, a little girl, spent those first days and weeks, her fun-loving father dead, her mother simply “away.” Nancy returned to her daughter and family after the overdose, “very depressed,” moving out of the one-story home on Broad Street and back into the Schraffenberger house on Main. Nancy kept the clothing store for a while, leaving her daughter to the care of my mother’s grandmother and maiden aunt.

“I was closer to Sissie and grandmother because they were always at the house, but I don’t think their parenting mattered much to me. The void was still there.”

Nancy shut herself off from the wives and men of the Legion, going back inside herself and inside the stately home with its hand-embroidered linens and inlaid cherry floors.

I have spent long afternoons lying next to my grandmother on her bed. She would tell me stories of her life, as she circled her wrists in the air and bobbed her knees to work out the slow-burning cramps of arthritis. The few occasions she mentioned her lover and husband, she called him “Dad.” She would reveal him to me as a character in a story, nothing more.

If my mother mentioned the men of her family, it was her Uncle Tom or, more fondly, her grandfather, George, the man she claimed for her heart after her father’s death. It was George who took his granddaughter to Sunday brunch and for meandering rides in the country.

“I always knew I would get a treat at the end of the day,” she tells me, smiling, “but only if I didn’t ask for it. That’d be cheating!”

In exchange for Nancy’s work in the flower shop, Uncle Tom paid my mother’s tuition at Stephen’s, a women’s college in Missouri. But Shirley was often miserable so far away from her Ohio home, lonely with a low ache soothed by the comforting decorum of teas, and by the soft hymns that filled the college chapel during mandatory vespers each Wednesday evening. I have a letter of hers to her mother. She promises to apply herself more, to study harder. In the middle of her freshman year, Shirley lost her grandfather. She has told me she remembers nothing of the train ride through the night that carried her from St. Louis back to Cincinnati.

It is only the women of my mother’s family that remained for them and for me. John Miller was dead, George had passed, and Uncle Tom had moved to California by the time I was born. He’d met a beautiful cabaret singer in Chicago named Irene and married her and adopted her son, John, as his own.

My great-aunt, Ada Louise, hated her name so much she requested the family called her “Sister,” which further devolved for me into just “Sissie,” the woman who hand-sewed my lavender princess costume for a stateside Halloween. My grandmother told me with a straight face she’d been christened “Nancy Virginia Alaska” and she lied about her age, trimming two years off her birth date of 1898. She was the one who would sneak me soft cheddar cheese and crackers and a small glass of dry sherry in the afternoons at her house. I couldn’t have been more than nine or ten. She was the one who took me out to fancy lunches in Cincinnati in adult restaurants with her bridge-playing friends. Living in the midst of our fierce and innocent love for each other, my mother always told me “you’re more of your grandmother’s child than mine. You’re very much like her.”

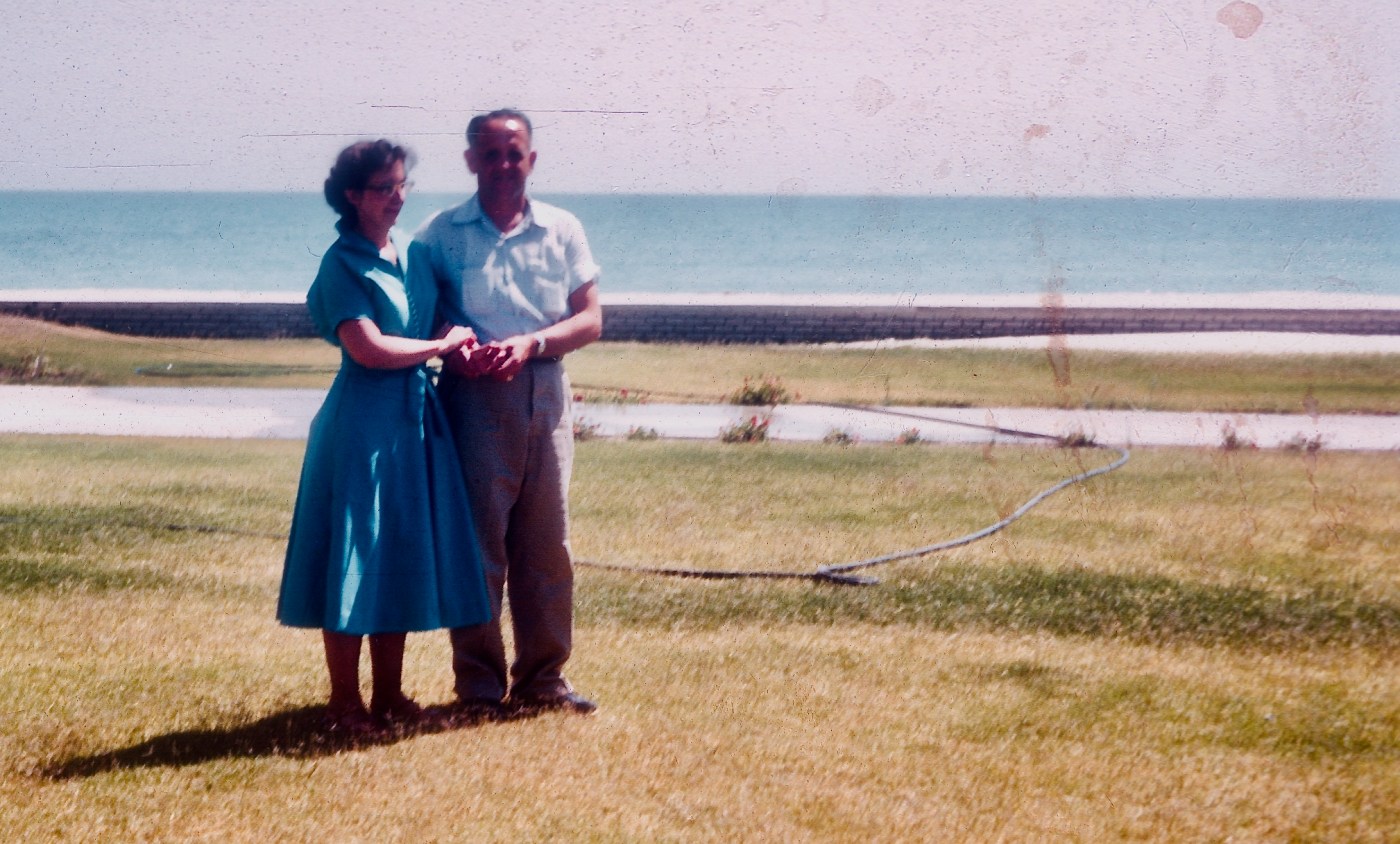

By the fall of 1953, Shirley had been teaching school across the river in northern Kentucky for several years after taking her degree from the University of Cincinnati. She came home each day to her mother, to the small cottage in Ft. Mitchell where they lived.

“I only knew that if I didn’t get out then,” she told me tersely, “that I’d never leave!”

I’d asked her when and why she decided to travel halfway around the world, to Saudi Arabia, and all I got was this answer full of desperate energy. Had she caught some import or had she simply bolted on an unexplained but strongly felt instinct of survival?

“I wanted to try my own wings, and I knew if I stayed in the States, my mother would follow me. Maybe my mother was making up for lost time, but she loved my father so much, there wasn’t ever room for me.”

It seemed to me life had dealt her a lousy hand of losses, and she was finally ready to deal herself a new one. Where did she find the courage and energy to play another round? I never heard my grandmother criticize my mother’s decision to go. But each time we left the States, I can remember their tears erupting, quietly and unbidden, days before our final good-byes at the airport. Their lives had been full of leave-takings and no one in my family does them well.

But the Schraffenberger matriarchs were not timid women, and there was a steady curiosity in my mother. Grandma and Sissie had it, too. I still have Sissie’s travel journal from a trip around the continental United States sometime in the 50’s. She even visited in Yelapa, a tiny cluster of thatched houses on a crescent beach south of Puerta Vallarta on Mexico’s Pacific coast. I remember my grandmother’s trip to Spain and Portugal in Sissie’s company. Nancy Schraffenberger Miller may have told my mother to cross the street when she saw a black cat and told my mother that girls from nice families didn’t babysit, but she’d worked outside her home most of her adult life. I have a picture of her on horseback. Maybe it was a mule, but she was astride! So it wasn’t a big surprise that her daughter took a college degree at the University of Cincinnati, cooking for a fraternity house to make a little extra money, and worked for seven years before her marriage.

My mother had grown up around the Manchester Hotel, filled with the commerce of people and goods, a place populated by travelers and men and women of the trades. It may have been the legacy of “Aunt Hattie” that she claimed. The woman was no family relation, just the hatcheck lady in the hotel’s lobby. My mother would go sit with her, the biggest treat coming when Hattie would allow her to take the coats and return the bowlers to the patrons of the place. It was my mother who taught me to people-watch, and I believe it was this lifelong fascination with the comings and goings of the world that put going overseas into the realm of the possible.

Shirley exchanged her northern Kentucky classroom for one in eastern Saudi Arabia. She and a vivacious fellow teacher, Norma LaBelle, planned modest adventures, taking off on one vacation for Kashmir and India. They lived on a houseboat at the edge of a Himalayan lake, wandering through the local ruins, and buying up treasures from the bazaars. By the end of her 18-month contract, she was ready to return to the States.

My father, Bill, was raised a country boy in southern Illinois. William Edward Ayers, Senior and Ione Marie Honey brought nine children into the world. The gravestones behind Fountain Presbyterian Church up from the creek hollow behind the farmhouse bore dates of early deaths for four of them. Their first child, Merle, born in 1901, only lived four hours. Teddy lived less than a year, living and dying in 1918, the year my father turned three. My father’s sister told me Ione was grieving so hard Bill got fed and clothed but little else. Maurillion died of scarlet fever in 1921 when my father was six. My grandmother’s favorite son, John, died in 1931 at the age of 26. Ione almost lost her mind.

The small family farm was just outside the town of Marion. “Bloody Williamson County,” they called it, and my father’s stories gave witness to the times. His older brother, Gray, was a government agent during Prohibition and one night, the Shelton Gang turned the tables on Gray. There was my father on the front porch, and here come Gray, with the Shelton brothers right behind him, firing their Tommy-guns into my uncle’s ’25 Dodge Coupe. It was one of my father’s most shocking dinnertime stories.

My Aunt Vesta figured most prominently in my father’s happy tales. Vesta could make my father laugh, her most precious gift to him and to me. There was that horseback ride through the woods when Vesta grabbed a branch and let it snap back in my father’s face, knocking him off his horse and into the creek bed. It was only a slight concussion and a broken arm, but my father artfully milked the occasion, letting Vesta think she’d killed him. Another time, some minor offense still strong in her head, Vesta took her mother’s kitchen shears and clipped all the luxurious hair off the tail of my father’s favorite dog. Revenge was swift. My father laid in wait with the largest garden potato he could find, winging the tuber into Vesta’s rib cage as she came around the corner from the barn. Vesta fell to the ground, not moving.

“Mama, mama, I kilt Vesta,” my father screamed, running breathless and scared into the hot kitchen and toward his mother’s salvation. Vesta was not dead but she and my father both earned a licking from their mother.

“Mrs. Ayers,” said a neighbor once, shaking his head, “those kids of yours are gonna kill each other.” Ione knew better.

I heard more tales in the winter of 1993, when my Uncle Art became one of two left to tell them. Vesta had died June 28th and now my father was dead, six months to the day from his sister’s death. I shared with Uncle Art, my favorite, that sometime in the fall I had this image “inserted” into a dream, like a flash frame, of a severed leg. I’d never dreamt of anything like it before. Uncle Art lowered his chin and smiled at me.

My Uncle Art was a Methodist minister of great gift. When he read scripture it was like hearing good Shakespeare. He didn’t sit in the rhythms of the Psalms, lazy and thoughtless. He read them as if he was the first one to speak those words. Urgency, not habit, propelled his inflections. His voice would rise and fall with the line not as it was written on the page, but as it was felt at the heart. He didn’t sound like anybody else. And he had a flair for the dramatic. My first introduction to a tenebrae service during Holy Week was at his church in Virginia. As the lights were dimmed at each successive reading, symbolizing the astonishing and tragic descent toward Good Friday from Palm Sunday, my eyes were glued to the twilight of the altar where a cross was draped in black silk and black roses lay at its feet – where’d he find such a thing? At my Uncle Art’s services, he wanted you to not only hear the Word but sense it and see it, feel it and take it home with you.

At my mother’s kitchen table on that New Year’s Eve, Uncle Art took me back to the Battle of Hastings and a soldier named Truelove. Duke William was thrown from his horse and had his helmet “beaten into his face.” According to the “Deeds of Battle Abbey,” a manuscript bought and salvaged by one Thomas Thorpe, a book collector in London:

It’s been written that another Truelove fought later in the next century with Richard Lion Heart in the Third Crusade. Stories of beginnings are like that: they are for the heart not the history books. Just because it is apocryphal doesn’t mean it’s not true. Through shrouds of cigarette smoke and sips of single malt scotch, my favorite uncle laid down the stories he had carried for so long and dropped them in my grateful lap. He rambled as comfortably as the clock, past the original Ayer land grant in Derbyshire, through a line that moved south to Salisbury. In 1635, there was an ocean crossing to New England on a ship called the James and a settling near the Massachusetts-New Hampshire border. A son moved to Basking Ridge, New Jersey and another generation to Virginia, then to Kentucky and finally southern Illinois. The women? They were Cornish and Irish and German and, my Aunt Vesta swore, Cherokee. I have found no evidence of Native American ancestry but wished it so!

My father was the spitting image of his father. “If there was a dirty, thankless job to do around the farm, Dad would set Bill to do it,” Art told me.

And William Senior could be mean, very mean. One fall day, he presented Art with a wagon-full of deadwood out of the scrubby forest behind the house. With my father watching, William Senior ordered Art to stack the heavy logs in the barn for the winter. Art was only eight or nine years old. William Senior dumped one particularly large and odd-shaped mass of wood off the back of the wagon at Art’s feet.

“Get busy. The job’s got to be done by dinnertime.”

The silence in the faded red barn hung there in challenge. William Senior waited. My father walked over to the gnarled piece of wood, and turned toward his younger brother.

“Here you go, Art, if I help you, we can make it to the kitchen table on time.”

William Senior took his own stony thin-lipped face and walked out of the barn without a word.

My father laid down his childhood over and over again, according to Art, and took up the burden of shielding his siblings from the cruelties of a man he never understood.

His mother, Ione, was his own private saint. God, I would have liked to have known her and her sisters! As their own mother lay dying, she and her sister, Cecelia, waited by her bedside through all the pain. After long days without resolution or relief, the daughters made a decision. I wonder if they talked about it beforehand. My great aunt took a syringe from the bedside table, drained the remaining morphine, and emptied it into her mother’s veins.

This was the same Aunt Cec that took my father in during his last years of high school. “My angel child,” she called him, and her home was a much-needed escape. Uncle Art did not say exactly what had prompted the rescue, but rescue it was. It would be forty years before my father returned to the family farmhouse.

“My God, she worked hard,” my father would tell me, prefacing each mention of his mother with that tribute. But that was all I heard of her. I heard of her stewed tomatoes, her buttermilk, her fried chicken, her medicinal plasters and her frustration at yet another broken bone when her son, Bill, would arrive home with a limb askew. How she nursed and how she cooked, nothing else. She was dead of cancer by the time I was born, but my father has her smile. William Senior was alive when I was born and saw me once. There are no smiling pictures of my grandfather.

My father loved music, and swept the dance contests at the local high school. He excelled in math and poetry and Latin.

“Amo, amas, amat,” he’d conjugate to me over and over again whenever we talked about school.

“I love, you love, he loves,” a translation that always hung wistfully in the air. I believe he ached for the shining vision of those words all his life.

My father would escape the stranglehold of that T-shaped farmhouse, but it was a complicated journey. He married a schoolmate, a woman who’d been christened “Lady Ione,” and with her, fathered my half-brother, William Edward the Third, and my half-sister, Marlyn Rae. Billy would inherit my father’s underlying generosity.

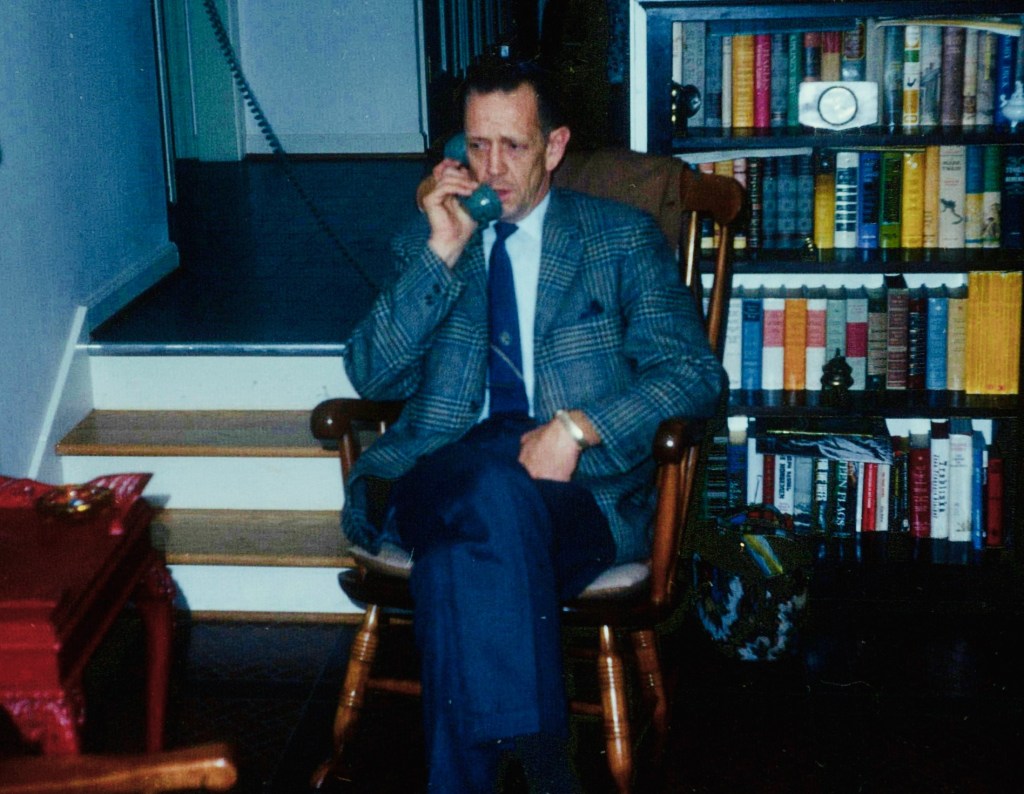

Marlyn lived out my father’s love of books, excelling in school, even writing poetry and songs in her later years. We shared this complicated man at different points in his life, our memories colored by his own shifting identity and our own. After high school, Dad went into the railroad business like his father and grandfather before him, becoming a certified fireman for the Central and Eastern Illinois line. As the railroads faded and automobiles took over the landscape, he was hired on at the Shell Oil refinery in Wood River, Illinois. My father was a self-taught engineer who brought to his craft a love of precision and a keen understanding of how things worked. He would come home from work in Dhahran and explain to me in animated detail how a thermocouple functioned. I couldn’t have been more than six or seven, but I knew what the inside of a butterfly valve looked like.

After the break-up of his first marriage, my father headed north to Detroit, and home to Vesta. f Dad was mourning the loss, he did not show it. Vesta always told me that as a child, my father would head off into the woods with his dogs and disappear for several hours. She tells of the time that he set a brush fire in the back yard to dispose of a pile of dead wood, only to realize to his horror as the flames climbed that a family of rabbits had a warren underneath it. My father grieved for days, she said.

In Detroit, he got a job as an electrician and it was his boss that shoved the Aramco want ad under his nose. Someone else paid for his suit for the New York City interview. He arrived in the Kingdom in 1954 to work at the refinery in Ras Tanura on the shore of the Arabian Gulf.

seriously good writing!

I’m ready for the next segment.